Nausea (Part 4): Famous Last Words

“Now and then I give such a big yawn that tears roll down my cheeks. It is a deep, deep boredom, the deep heart of existence, the very matter I am made of.” ~ Nausea

Nausea is the diary of Antoine Roquentin after he has settled in the fictional French seaport town of Bouville, having returned from years of travel. He aims to write a history for an 18th century political figure and during the exercise of reviewing another man’s life he accidentally slips into reviewing his own. He suddenly feels he is waking up from a dream. Everything that had filled or fulfilled his life up to this waking begins to appear meaningless. No longer can he swallow his own tales about the tinsel of travel and the seduction of women as a means to a happy existence. Place names and past love affairs seem to have been tampered with. Memories he expected to sustain him through life are dematerialising. The cinema reel has caught fire and he’s become suddenly aware of the projectionist.

It dawns on him in a park one day that he, along with every other particle of dust in the world, is entirely superfluous. He is in excess and not essential to anything. This characteristic seems to pervade his entire environment. Everything is oozing existence and for no reason at all. The world is trapped by a complete boredom, that might be escaped only through death, but incapable of killing itself. He has pierced Buddha’s infamous veil with which man clothes the world with meaning. But Roquentin is no Zen lunatic. He is a thinker, painfully intellectual, and stubborn down to the bone. So he fights a way through this maze with words. He thinks he might come to terms with it that way. But the visions grow more sickening, repugnant – nauseating.

The nausea and anxiety grow; a feeling of absurdity wells. The soul has spread to the ego that horrible little truth; a truth the ego tried to conquer: that nothing matters. This should be liberating, for Roquentin realises he is truly free, not tied to the world by any morals or meaning. But freedom has never looked heavier.

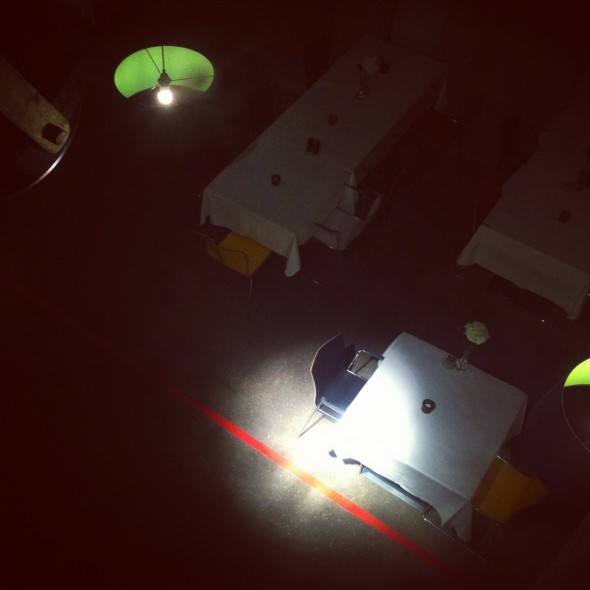

In a café, where most of his realisations occur – for boredom and idleness is the Great Revealer in this novel – Roquentin does not see people eating but people “reviving their strength to complete their respective tasks.” He sees that all people have a personal obstinacy which prevents them from noticing they exist, from noticing they are utterly superfluous, from noticing they are free. There is not one of us who doesn’t think he is indispensible to somebody or something. Be it the job, the degree, the government, the girl, the pet dog, the art form: man always find something to chain himself to. Roquentin, however, when he quits the history he is writing, is without all these things. He is drowning in a sea of freedom with not a rock to cling to.

He starts snatching at the ground of his elusive history, desperate for one acorn of truth, and nauseated by that long and almost unending future, which is completely alterable, but meaningless. He hopes for someone to thrust something into his hands, something solid – a a circumstance large and unavoidable – anything to save him from the weight of his own freedom. But Roquentin knows he must choose for himself (especially if he is to jump Sartre’s great hurdle to freedom). In a cafe, as always, it comes to him. As a blues song plays on a gramophone and he hears the record skip a little, but in his head the melody continues. He realises art escapes the physicality of the universe. It survives decomposition; it’s a pillar of permanence. And so it comes to him that he must choose the life of the artist, and he imagines he might write a novel. Like Camus suggests in the Myth of Sisyphus, the absurdity of art seems the only weapon against the absurdity of existence; perhaps the biggest ‘fuck you’ to nothingness we’ve got.

But Roquentin has already written the novel. It is his diary – which is the novel Nausea. He is already the artist. Are his descriptions of the nausea his weapons against it or part of the malady’s cause? What I mean is his life as an artist making him nauseous?

“Thirty years old! And an annual income of 14 000 Francs. Dividend coupons to cash every month. Yet I’m not an old man! Let them give me something to do, no matter what…I’d better think about something else, because at the moment I’m putting on an act for my own benefit. I know perfectly well that I don’t want to do anything; to do something is to create existence – and there’s quite enough existence as it is. The fact is that I can’t put down my pen: I think I’m going to have the Nausea and I have the impression that I put it off by writing. So I write down whatever comes into my head.” ~ Roquentin

* * * * * *

Am I nearing a conclusion? I do not know. I do not want to pretend. Anyone who has read this series can see I’ve done quite enough of that!

The nausea may have ended if Roquentin had stopped poking at it with his pen. He believes he can kill it with a novel, but perhaps it is the act of stopping writing which ends the nausea..? If he had quit poking earlier I would not have found his diary on a book shelf after tossing a university course reader across the room a year ago. And presumably I would not have begun this blog (my own nausea). It seems in the effort to obscure nausea with art, art creates nausea! And a lot of virtual sick bags for people to catch it from.

So do I end now and pin ideas of a future artwork like a sheet between me and that interminable present? Do I hide from the nausea, from existence, from freedom, and dispose myself to art in no different a way to what I’d do for any other activity…? To me it’s philosophically equal to all other activities; just a task to help you forget you exist.

* * * * * *

I couldn’t have picked a worse novel to attempt to cure my own nausea with. One of philosophy’s least humble and most headstrong writers. I would have been better off if I had read Camus again, and connected with his undercurrent of Catholic mysticism. No I don’t care about Catholicism! But there’s got to be some magic in it somewhere…and Nausea was completely godless. The universe can’t be so atheistic as to become dogmatic; it is too imperfect for that.

Actually, that is not entirely true. In Nausea there were moments where Roquentin seemed to smell ‘something else’; the prickling of possibilities, or a kind of mystique. But it seemed he could never follow the scent too far while on Sartre’s leash. Roquentin calls it the “feeling of adventure”. But under this banner he groups two vastly different experiences: the feeling of adventure when recounting events and the feeling of adventure when completely present in events.

He says, “for the most common place event to become an adventure, you must – and this is all that is necessary – start recounting it. This is what fools people: a man is always a teller of tales, he lives surrounded by his stories…he sees everything that happens to him through them; and he tries to live his life as if he were recounting it.”

From tales of his life’s events man gains a tingling feeling. But he is deluded; it is a superficial high. Roquentin tells us this, but he forgets it himself by the end of the novel, choosing instead to recount. He says,

“The feeling of adventure definitely doesn’t come from events: I have proved that. It’s rather the way in which moments are linked together. This, I think, is what happens: all of a sudden you feel that time is passing, that each moment leads to another moment, this one to yet another and so on; that each moment destroys itself and its no use trying to hold back, etc. etc., and then you attribute this property to events which appear to you in the moments; you extend to the contents what appertains to the form. In point of fact, people talk a lot about this famous passing of time, but you scarcely see it. You see a woman, you think one day she will be old, only you don’t see her grow old. But there are moments when you think you see her growing old and you feel yourself growing old with her: that is the feeling of adventure.”

Is this the feeling I discussed in Virginal Highs? I see no better way of putting it, without going all New Age on you. Perhaps music was an adventure I simply sniffed out. But I assigned to the events feelings that were actually coming from the method I used discovering it. How do I again find that flow of moments… I recall periods of life where I seemed to follow a path of coincidences, along a trail so thin it was almost invisible. Did I begin to confuse it with something meaningful? Can there be an intended path that has no meaning? — I feel so. Like being led by a golden thread, coming out from the navel. You might not see far ahead, but it would be enough to keep moving.